Today I want to talk about teaching letters and letter sounds to beginning readers. A strong alphabet foundation is beneficial, no matter what teaching method you are using. Learning letter sounds even helps children develop their sight vocabularies at those early reading stages, before they’ve learned to decode words. See these posts about early reading stages:

I teach the letters of the alphabet and their dominant sounds from the get-go, no matter what stage the child is reading on.

Assessing Letter Knowledge

Want to save some instructional time? Before you begin teaching letters to new students, give them a quick assessment to see which letters they know. That way you won’t waste time teaching letters unnecessarily. As you assess, if you notice that a youngster can remember letter sounds better than letter names, or vice versa, note down such preferences and take advantage of them in your lessons.

Introducing Letters

Always introduce letters in a multisensory fashion.

- visual: Children see the letter form, see the key word image, and watch you form the letter.

- auditory: Students hear you and themselves say the letter and its sound.

- verbal: Youngsters say the letter name, key word, and letter sound; or say a mneumonic jingle while forming a letter.

- kinesthetic/tactile: Children trace or write a letter in the air, or on a vertical or flat surface. They can trace sandpaper letters or form letters in sand or rice trays.

Combine these methods when you can. For instance, have the child try saying the name of the letter while writing it. If you find a combination of approaches that works best for a given child, continue presenting letters that way. You may find that some youngsters can only use one modality at a time, though.

Order for Introducing Letters

Have a plan for presenting new letters in a purposeful sequence. Some teachers introduce one letter a week in alphabetical order. But often by the time the 26 weeks are up, children forget the first letters they learned. If this method works for you, by all means continue with it. But if you are looking for alternatives to letter-of-the-week sequence, here are some research-based possibilities:

- Some teachers start with consonants whose sounds can be easily extended and are therefore optimal for learning decoding: m, s, f, r, n.

- Others start with letters whose sounds are easy to learn because they are embedded at the beginning of the letter name (b, soft c, d, soft g, j, k, p, t, v, z).

- Next easiest are the consonants whose sounds can be heard at the end of the letter name (f, l, m, n, r, s).

- The most challenging consonant sounds to learn are those whose letter names have nothing to do with the sounds (hard c, hard g, h, q, w, x). I make up silly names for some of these difficult letters (e.g., haitch, wubble you).

- Of course vowels are in a category of their own. I start with short vowels, because that’s what I teach first in my phonics lessons.

- Another approach is to introduce letters that are easiest to write first. But I encourage you not to rush having your students write letters, especially complex letters. It’s better to wait than to inadvertently establish bad writing habits.

- If you are tutoring, you may want to start by teaching the letters in the student’s name.

- Unfortunately many parents and teachers start by teaching uppercase (capital) letters. I urge you not to do this. When children learn to write their names in uppercase letters, it becomes a difficult habit to break later. Start by teaching lowercase letters. Kids will see and write lowercase letters far more often than uppercase letters, so they are more profitable to teach. An exception to this “rule” is teaching the uppercase letter at the beginning of a child’s name.

Reviewing Letters

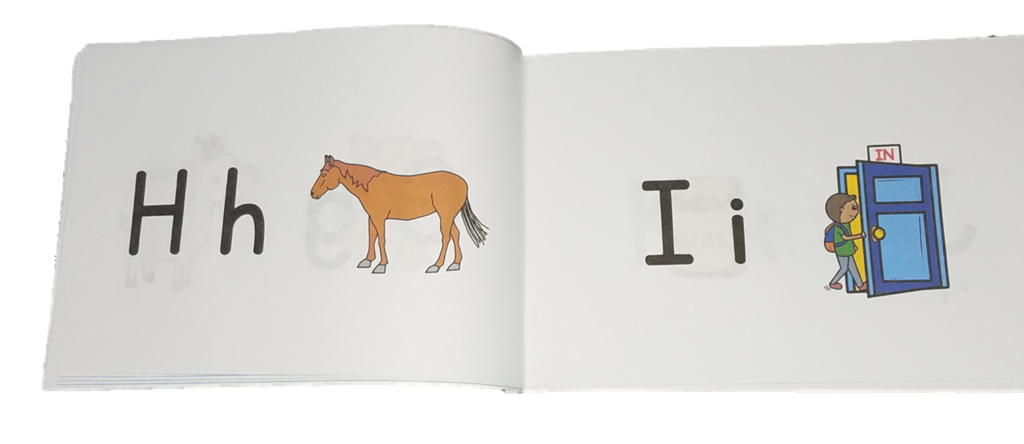

Alphabet books are great way to collect letters that you have introduced to a child. I like ABC books with the uppercase letter, lowercase letter, and key word image. I teach the child to say the two letter names, the name of the image, and the beginning sound of the image.

H – h – horse – /h/ [beginning sound of horse] Isolating the first letter of a word is good phonemic awareness practice and shows the student how to use the key word to get to the sound of the letter. You can review the alphabet book at the beginning of every lesson, and your student can take it home for extra practice.

If you are teaching a small group in person, a paper alphabet book with preset key word images like the one above might work best. If tutoring one child in person, you can start with a blank book and have the student select images of their choice for key words from a pile. The easy-to-assemble printable ABC book above comes with both options–an alphabet book with images, and another with no preset key word images. The resource includes pages of full-color cut-out pictures for children to choose from. You can paste them into the youngster’s alphabet book.

If you are teaching online, a digital alphabet book has many advantages. For problematic letters, you can duplicate pages and drag and drop them to the beginning, middle, and end of the book for repetition. Similarly, you can delete the pages for letters that have been mastered or drag them to the end of the book for later review. It’s also easy to make different copies of digital alphabet books for different groups or students.

Another way to review letters is with letter cards. You can quickly sort the cards into known and unknown piles during the lesson. For each student or group, keep a running stack of cards for new and not-quite-known letters. Mix new cards into the deck, and put aside the known cards for long-term review later. Cards can be incorporated into games, as well. (See below.)

Teaching Challenging Letters

Many children have “problem letters” that they can’t remember. Sometimes this difficulty is caused by us, the teachers. Perhaps we presented letters that look alike one after the other (e.g., b and d) or introduced letters that are difficult to remember too soon. Try to save challenging letters for later lessons, and space out the introduction of letters that look similar.

One way to help kids master challenging letters is by reading individual letter books to them. These are books that show a given letter in several different words, along with images. Make sure you are using multisensory approaches when reviewing the letters, or try introducing a method you haven’t previously used, such as using a wet sponge pen to trace over (and erase) a letter you wrote in chalk.

Kids get a kick out of this approach. Pointing out the size and position of letters can also be a boost. I explain that there are three types of letters: trees, bushes, and carrots. It’s reassuring when a child reminds himself before writing, “It’s a carrot letter.” Come up with any memory tricks you can think of. For writing and identifying lowercase-b, I have said, “The bat comes before the ball.” Then I have the child practice writing the letter while saying, Bat before ball, bat before ball… For writing lowercase-d, I explain that c comes before d. Many teachers use the bed trick. Use whatever works! If you feel you have tried everything, and the letter is still elusive, then just skip it and come back to it after you have introduced the other letters.

One way to reinforce letter knowledge is to have your student practice writing the letters they have learned on an easel, chalkboard, whiteboard, or any reusable drawing device such as Magic Slate. You can provide writing practice of all the letters that start at the top and go down, or all the letters that start like the letter c. Encourage the child to say any jingle you have taught them, if that seems to help. After students have learned a few letters, you can begin presenting several letters at a time for other forms of letter work. One activity is to place several magnetic letters on a tray, and have the child find the letter or letters you name.

This can also be done on paper. They can also match uppercase to lowercase magnetic letters, letter tiles, or letter cards; match letters to key word images or other images that begin with the letter’s sound; or find magnetic letters with certain shape elements (lines, circles, curves, crosses, or dots). An important step is to have the youngster find certain letters in books they are reading, or in a large print book that you are showing during shared reading. Make the suggestion in an excited voice: “Oh, wow! I see the letter a on this page! Can you find it?” Also be sure to point out letters in sight words you are teaching the child or group. Last, but not least, you should incorporate the letters you have taught into short words for teaching decoding. You may want to take into consideration the way you will teach decoding, when you decide on the sequence for introducing letters. For example, if you know you are going to start with short-a CVC words, then you will want to introduce a and the consonants you plan to use in your decoding lessons. By the way, don’t think that you have to introduce all the letters before you start teaching phonics! If you feel the students are ready, start teaching them to sound out words with the letters you have taught. It’s also fruitful to demonstrate to children how to use their knowledge of letter sounds to spell phonetically. In shared writing, show students how to isolate the sounds in a word. Practice the phonemic awareness skill of isolating sounds. If the kids can’t identify the letter that goes with the sound, try mentioning the key word you have taught them. These words are called key words for a reason!

Games

It’s fun to liven up your lessons with games–educational, of course. Personally, I like to use my own games rather than those found online, because too often the games that come up in search are too challenging or do not use the letter forms that correspond with the ones I am teaching. During the lesson, I let the student know that, if we accomplish everything I planned for the lesson, we can play a game afterward.

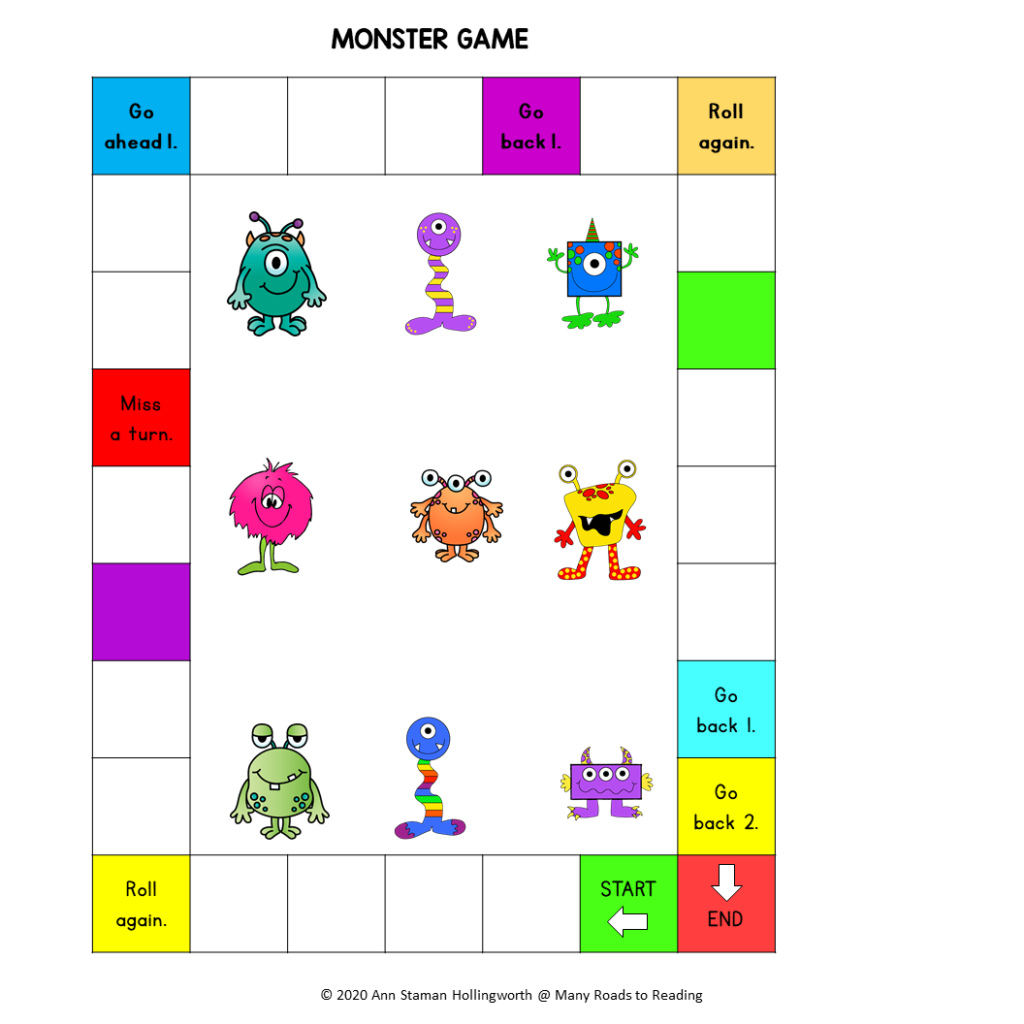

One easy way to create a game is by making a game board. You can draw the board yourself or download one from Teachers Pay Teachers. If you make the game board yourself, be sure to include spaces that say something like, Go back one step and Go ahead two steps and include forward and backward short-cuts, to make the game more exciting!

I use board games for whatever I am teaching–phonetic words, sight words, or letters on cards. If the child can identify the letter I show them, they can roll the die or dice and take that many steps. (For very young students, just counting the steps can be a learning experience if they haven’t mastered one-to-one correspondence yet!) If they are unable to read whatever I show them, then the turn passes to the next student. Or if I am tutoring the child, then I get a turn to roll the die. It’s also possible to play a memory game or modified Go Fish with two sets of letter cards.

The card resource at the left includes letter cards that are designed just like playing cards. For particularly active students, you can play games that allow them to move. I play a modification of Mother, May I? with letters and words. The child stands on one side of the room, touching the wall. For each letter they identify correctly, they can take one step toward me, or toward the other wall. This is a fun game to play outside during good weather, while you are waiting for a parent to pick up the child after a lesson. Another type of game that’s actually more of a puzzle is to play a modified Twenty Questions game. Place a dozen or more magnetic letters of different colors and shapes on a tray. Then have the child guess the letter you are thinking of my asking Yes/No questions about the color, shape, and case of the letter:

- Is it red?

- Is it uppercase?

- Does it have a line in it?

You can also see how many examples of a given letter the student can find around the room. These are just a few of the fun activities you can play with a child with little or no investment of your time or money.

Keep It Easy

Whatever reason you are working with beginning readers, it’s important to keep your lessons easy and fun. This is especially true if you are tutoring a child who is encountering difficulties in the classroom. We’ve already talked about how to adapt the lessons to the student’s preferred modalities and learning strengths, but we need to pay attention to their psychological well-being, too. A youngster may already feel inadequate about their ability to learn, and the last thing you want to do is intensify that attitude. Students have very different abilities to tolerate risk and unfamiliarity. If you sense any discomfort or reluctance in the child, back off a bit. Focus on the known and only gradually add anything new. Play a few more games. Point out the youngster’s accomplishments. Drop down a level or two in reading. Read to them, as well. Sometimes it helps to explain to a child that learning to read is like climbing a ladder. It takes energy and doesn’t happen all at once. Each time they work hard at learning without giving up, you can tell them that they moved up the reading ladder. Soon they will be asking, at the end of a lesson, Did I move up the reading ladder today? Hopefully you can respond that they certainly did!

Have any students who are having difficulty learning to read? I don’t know about you, but every year there seems to be one student I especially worry about. Click here to grab 20 TIPS FOR TEACHING STRUGGLING READERS for free!

Leave a Reply