Farrah has come to the word standing in her book. She has progressed to the point where she doesn’t have to read all 7 phonemes in the words sequentially: /s/-/t/-/a/-/n/-/d/-/i/-/ng/. She can identify the word almost immediately because she can see the bigger chunks in the word: st-and-ing > standing. Farrah can do this because she is in the Consolidated-Alphabetic stage.

Farrah has come to the word standing in her book. She has progressed to the point where she doesn’t have to read all 7 phonemes in the words sequentially: /s/-/t/-/a/-/n/-/d/-/i/-/ng/. She can identify the word almost immediately because she can see the bigger chunks in the word: st-and-ing > standing. Farrah can do this because she is in the Consolidated-Alphabetic stage.

READING STAGES

You may have read one or more of my previous posts about Linnea Ehri’s reading stages:

Teaching the Pre-Alphabetic Reader: Early Sight Words

Teaching the Partial-Alphabetic Reader: Phonetic Cue Reading

Teaching the Full-Alphabetic Reader: Cipher Reading

Dr. Ehri has spent her career researching the stages that children go through when learning to read. These stages overlap, so they are often called phases. By adjusting our teaching to the phrase the youngster is on, we can help them move smoothly through it and on to the next one.

Here are brief explanations of the first four stages that Ehri’s research points toward. The names she uses to describe the phases reflect the new or predominant connections children are making as they read words:

-

- Pre-Alphabetic: Children know few if any letter-sound correspondences and are not ready to analyze words phonetically. They rely on learning words as wholes and guessing from partial visual cues and context. (PreK-K)

- Partial-Alphabetic: Readers know some letter-sound correspondences, but can’t decode whole words. They might use partial phonetic cues—often 1st or last letters—along with the context—to figure out words. (K-1)

- Full-Alphabetic: Youngsters use a full decoding strategy to identify unfamiliar words—either phoneme by phoneme, or by analogy. (1-2)

- Consolidated-Alphabetic: Students are more skilled at decoding and can recognize larger chunks, such as morphemes or syllables. (2-3+)

Although I do not agree with all of Dr. Ehri’s research conclusions, I have noticed that that many, if not most, of my students have passed through the stages she describes. Thus, I have been able to use her suggestions to adapt my teaching to best help young readers progress. I’d love to help you do the same with your students.

THE CONSOLIDATED-ALPHABETIC PHASE

By the end of the Full–Alphabetic stage, readers have mastered most or all of the grapheme-phoneme correspondences and can decode phoneme by phoneme. They can read independently, but have more to learn in the next stage.

When youngsters move to the Consolidated–Alphabetic (C-A) phase, they can can now often read in larger (consolidated) chunks, or units, so their reading is more efficient. The Consolidated phase is also described as orthographic, because readers in this stage begin to focus on spelling patterns.

Let’s look at the types of chunks C-A readers use:

-

-

-

- onsets and rimes/spelling patterns

- one-syllable sight words

- morphemes

- syllables within multi-syllable words

-

-

1. Onsets and rimes

In a one-syllable word, the rime is the vowel or vowel combination and all the consonants that follow it. The onset is the consonant or consonants that precede the vowel, if there are any. Some words don’t have onsets.

-

-

-

-

-

-

- and

- b -and

- st -and

- str -and

-

-

-

-

-

Readers in the C-A stage, like Farrah, can see these chunks in words, either because they have naturally progressed to this point, or because they have been taught to look for onsets and rimes.

2. One-syllable sight words

Youngsters’ familiarity with onsets and rimes also helps to add words to their sight vocabularies, and, in turn, the words they know by sight help them read words in chunks. Two- and three-letter sight words such as the following can be quickly recognized as rimes in longer words by students at this stage: it, at, in, an, all, and and.

3. Morphemes

Morphemes are the smallest meaningful units in our language. All words are morphemes because words carry meaning, but some word parts can be morphemes, too.

The word cats is made up of two morphemes: cat plus the plural inflection, -s. Unhelpful has three morphemes: un-, help, -ful.

Morphemes include:

-

-

- all words, including those within compound words (e.g., firefighter)

- base words – words onto which prefixes and suffixes can be added (e.g., jump)

- roots – parts of words that do not stand alone, onto which affixes can be added (e.g., struct)

- affixes – prefixes and suffixes (e.g., pre-, -ful)

- inflections – types of affixes that change number or time (-s, -ing, -ed, -es)

-

4. Syllables within multi-syllable words

Usually the last chunks that C-A readers learn are syllables within words of two or more syllables. A syllable is a segment of speech that contains a vowel sound and may or may not contain consonants. A written syllable may also contain unsounded vowels.

Some examples of syllables within longer words are run-ner, a-way, and im-por-tant. Note that syllables do not necessarily have meaning the way morphemes do.

USE READING STAGES TO HELP READERS MAXIMIZE THEIR LEARNING

What I love about developmental reading stages is that, once we figure out the stage a reader is on, we can adjust our teaching to help them progress more efficiently. We are not holding them back, nor are we pushing them too fast to learn something they aren’t ready for. There are three main ways we can use stages to help students:

-

-

-

- Introduce words most appropriate for that phase.

- Teach strategies for learning at that stage.

- Nudge the students toward the next phase.

-

-

HELPING THE CONSOLIDATED-ALPHABETIC READER

1. Introduce words most appropriate for the Consolidated-Alphabetic stage.

The words to focus on during reading instruction at this stage may appear in the books your students are reading, but you will also want to provide isolated activities to reinforce children’s awareness of longer units in words. Bring these words and word divisions to the attention of your students, if you haven’t already. Review vowel and consonant sounds, as needed.

- high frequency words with one or more syllables

- words with inflectional endings (cat, cats; play, plays, playing, played)

- words with common roots (play, player; happy, happiness; help, helpful, helpless)

- words with common rimes or spelling patterns (e.g., cat, mat, rat; and, band, stand, strand; sing, bring, swing, string)

- words with common prefixes (e.g., redo, remake, rewrite)

- words of different syllable types:

- open (go, me)

- closed (got, met)

- silent-e (made, like)

- r-controlled (car, fort)

- vowel digraph (goat, meat)

- -le syllable (little, ladle)

- multi-syllabic words (into, today)

2. Teach strategies for learning at the Consolidated-Alphabetic stage.

When they begin processing words in chunks, children become more proficient at the reading strategies they used before, and they can also take on new strategies.

The techniques below are certainly not listed in order of priority. In fact, they are interrelated and overlapping, so you will certainly be teaching some of them at the same time. Below are summaries of the approaches.

Analytic and Analogic Decoding

You may have introduced basic analytic and analogic decoding when your students were in the Full-Alphabetic stage. Children become even more adept at these approaches when their awareness of onsets and rimes broadens in the C-A stage.

With analytic decoding, readers analyze, or take apart, one-syllable words by looking at the onsets and rimes within the words. Words with the same rimes can be taught together as word families. Words in the -ake family, for instance, would include make, bake, take, and flake. Believe it or not, 36 rime spellings make up over 500 words!

As you can see, working with word families involves rhyming, so rhyming practice is helpful to your students at this stage. Here is an example of an approach you could take with teaching rhyming and word families.

Analogic decoding is a type of analytic decoding where you show readers how to figure out an unknown word by comparing it to a word they know. “This word book looks like the word look, so it must be /book/.” Readers get better at using analogies at this point because they know many more sight words and spelling patterns. This approach works best with children who have a decent sight vocabulary and working memory.

Hierarchical Decoding

Another type of decoding that C-A readers become competent in is hierarchical decoding. Instead of merely sounding out each letter sequentially, hierarchical decoders recognize that letters within a word can affect the sounds of other letters in a word. Here are some hierarchical decoding and encoding cues:

- silent-e

- hard and soft c and g

- doubling rule in spelling (cuter and cutter)

- spelling rule for dropping silent-e

- “I before E, except after C…”

- y-rule

You have probably taught some of these generalizations at earlier stages, especially the silent-e rule.

Orthographic Spelling

Learning word families helps kids with spelling, as well as reading. Once they have learned how to spell a given rime (orthographic spelling), all they have to do is add the onset to figure out to spell a word phonetically. As readers progress, they will begin to take on more advanced spelling patterns such as ight words.

Learning Longer Sight Words

When readers know more spelling patterns and begin to remember larger word chunks, their sight vocabularies expand, as well. They not only know more words by sight, but can remember longer words, as well. Less practice is needed to commit words to memory.

Encourage students to look for familiar chunks–even in words that aren’t entirely phonetic. Pointing out any nonphonetic parts of words will help youngsters remember irregular words (e.g., knew, through).

Morphemic Manipulation

Teaching morphemic manipulation is exciting because the payoff is so great. Once readers learn about adding and subtracting inflections and other affixes, they are typically more motivated about their reading development, no matter what level they are on. When beginning readers learn that going = go + ing, they can suddenly read a word that’s twice as long, and then begin to recognize -ing in other words. The same goes for the prefix un- or the suffix –ful for more advanced readers. Morphemic awareness tends to be self-propelling.

Instruction in morphemes expands students’ knowledge of word meaning and leads to better comprehension.

You can teach decoding through morphemic manipulation in several ways:

- Find words within compound words. Start with compound words composed of high frequency sight words (into, today, inside, outside); then progress to content words, once the students can decode them or know the necessary sight words (firehouse, grandmother).

- For known words with affixes, have the students identify the prefix or suffix; say the word without the affix; then say them both (or all) together, progressing from the simplest to the more complex (looking > look + ing; unhelpful > help + ful > helpful + un > unhelpful).

- For an unknown word with an affix, remove the affix or affixes; decode the base word or root; then add the affix(es) back on and say together.

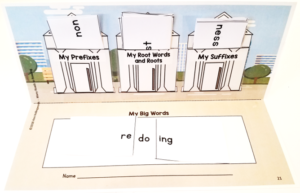

Have students keep journal entries for the affixed words they discover. This Word Part Journal is taken from Morpheme Cards, Journals, Banks: Prefixes, Suffixes, Roots K-6.

Have students fill in semantic webs, word webs, matrices.

Have students fill in semantic webs, word webs, matrices.

Use concrete materials for adding and subtracting morphemes. The kit below, taken from Morpheme Cards, Journals, Banks: Prefixes, Suffixes, Roots K-6, provides such an activity.

Use concrete materials for adding and subtracting morphemes. The kit below, taken from Morpheme Cards, Journals, Banks: Prefixes, Suffixes, Roots K-6, provides such an activity.

Here is a sample scope and sequence for teaching morphemic awareness.

Decoding by Syllable

A profound change that happens during this stage is that students learn to read words of more than one syllable. But, before they can do that, readers have to learn to recognize monosyllabic words by their syllable type. The 6 syllable types are listed above.

It’s helpful to teach children about syllable types, even if you don’t yet use the word syllable in your lessons. Readers are learning that the way words are spelled has an impact on how they are pronounced. One way to encourage awareness of syllable types is by having your students sort words according to their syllable type.

According to Ehri, readers in the C-A stage begin to be able to recognize different syllables in multi-syllabic words without being taught spelling rules, through “implicit awareness” that breaks come between certain letters. Teaching syllabication rules, she has found, is not particularly effective. Instead, she has youngsters look for spelling patterns in words and segment between the different spelling patterns.

One series that approaches multi-syllabic words this way is Megawords, by Kristin Johnson and Polly Bayrd. I find this approach very effective with students at the C-A stage.

Here is a possible sequence for teaching syllabication to your students:

- compound words

- two consonants between vowels

- closed/closed (tennis)

- closed/open (kitty)

- closed/silent-e (invite)

- closed/r-controlled (letter)

- one consonant between vowels

- open/closed (basic)

- open/silent-e (decide)

- open/r-controlled (paper)

- open/open (baby)

- closed/closed (limit)

- closed/open (body)

- closed/r-controlled (never)

Using syllable types can be helpful for both reading and spelling words–of either one syllable or more than one syllable.

3. Nudge the students toward the next stage. What is the next stage?

The last way we can use our knowledge of reading stages is to help nudge our students on from the stage they are on to the next stage. But is there a stage after the Consolidated-Alphabetic stage?

Later in her career, Ehri allowed that there may be a fifth stage, the Automatic-Alphabetic stage–when most words are known by sight, and when decoding is almost immediate. If students do encounter unfamiliar words, they are able to pick from a variety of decoding strategies which they can deploy quickly, if not automatically. As a result, students can now read fluently.

How do we nudge students toward the Automatic stage? To me, the Automatic stage is an extension of the Consolidated stage, so we should just keep teaching them the way we have been in the Consolidated stage. Teaching morphemic awareness to older students involves focusing on Greek and Latin roots. As youth go through secondary school, they will be exposed to more and more technical terms, and these roots are quite beneficial–both for deciphering terms, and for understanding their meanings.

If you don’t notice when your Automatic-Alphabetic readers don’t need your assistance with word identification any more, they will most likely let you know. Maybe they will point out discoveries about reading that you hadn’t thought of yourself! Or they might politely mention that the text you gave them was too easy. There will be plenty to still teach these students, but not much in the area of decoding words. Congratulate them–and yourself! Job well done.

At last we come to the end of our series of developmental reading stages, as outlined by Linnea Ehri. Her framework identifies stages of word identification, which is naturally only part of what we teach in reading, but I hope it has been helpful to you and to your students.

Happy teaching of Consolidated-Alphabetic readers!

References

Ebbers, S.M. 2017. Morphological awareness strategies for the general and special education classroom: A vehicle for vocabulary enhancement. Perspectives on Language and Literacy 43 (2): 29- 34.

Ehri, Linnea C. 2005. Development of sight word reading: Phases and findings. In M.J. Snowling and C. Hulme (eds.), The Science of Reading: A Handbook. UK: Blackwell Publishing, Ltd. https://doi.org/10.1002/9780470757642.ch8.

Ehri, Linnea C. 2015. How children learn to read words. In Oxford Library of Psychology: The Oxford Handbook of Reading (Alexander Pollatsek and Rebecca Treiman, eds.), pp. 293-310. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Retrieved on 11/28/2019 from https://psycnet.apa.org/record/2015-46178-020.Ehri, Linnea C. 2014. Orthographic mapping in the acquisition of sight word reading, spelling memory, and vocabulary learning. Scientific Studies of Reading 18: 5-21. https://doi.org/10.1080/10888438.2013.819356.

Ehri, Linnea C. 2017. Learning to read and spell words: How teachers’ instruction and students’ reading practices contribute to the development of reading and spelling skill. New York: Program in Educational Psychology: CUNY Graduate Center. Downloaded pdf 1/28/21: ER2017_LearningtoReadandSpellWords_Ehri.pdf.

Ehri, Linnea C. and Sandra McCormick. 1998. Phases of word learning: Implications for instruction with delayed and disabled readers. Reading and Writing Quarterly: Overcoming Learning Difficulties 14 (2): 135-163. https://doi.org/10.1080/1057356980140202

Henry, M. 2017. Morphemes matter: A framework for instruction. Perspectives on Language and Literacy 43 (2): 23-26.

Johnson, K. and P. Bayrd. Megawords: Decoding, Spelling, and Understanding Multisyllabic Words, 2nd Edition. 2010. Cambridge: School Specialty, Inc.

Moats, L. 2011. Morphology instruction for reading, spelling, and vocabulary. Focus: 28-30.

Wolter, J.A. and G. Collins. 2017. Morphological awareness intervention for students who struggle with language and literacy. Perspectives on Language and Literacy 43 (2): 17-22.

Leave a Reply