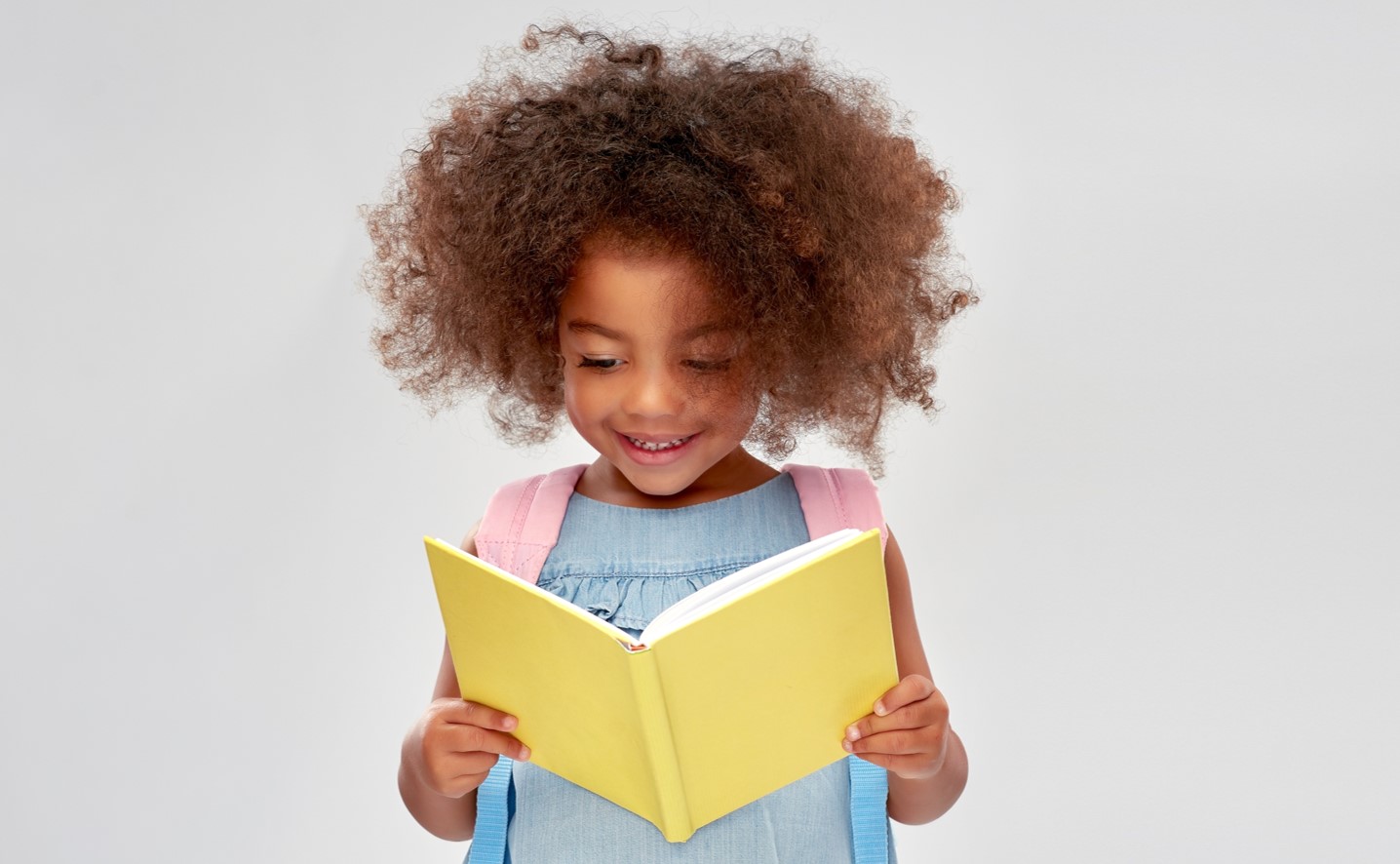

Seth is stuck on a word in a story. The word is irregular, nonphonetic. The letters in the word are not connected with their regular sounds, or at least the sounds he has learned so far at school. The word is night.

He tries to decode word phonetically, because that is his go-to reading strategy. He associates the letters with the sounds he knows: /n/ – /ĭ/ – /g/ – /h/ – /t/…./nig-hit/.

Seth is in the early Full-Alphabetic stage. He has learned to sound out words letter by letter, but doesn’t yet realize that there are some words that can’t be decoded that way.

READING STAGES

As you may recall from my previous posts, Teaching the Pre-Alphabetic Reader and Teaching the Partial-Alphabetic Reader, young children progress through different stages as they learn to read. These stages overlap, so they are often called phases. By adjusting our teaching to the stage the youngster is on, we can help them move smoothly through that phase and onto the next one. Linnea Ehri spent her career researching the stages that children go through when learning to read:

-

- Pre-Alphabetic: Children know few if any letter-sound correspondences and are not ready to analyze words phonetically. They rely on learning words as wholes and guessing from partial visual cues and context. (PreK-K)

- Partial-Alphabetic: Readers know some letter-sound correspondences, but can’t decode whole words. They might use partial phonetic cues—often 1st or last letters—along with the context—to figure out words. (K-1)

- Full-Alphabetic: Youngsters use a full decoding strategy to identify unfamiliar words—either phoneme by phoneme, or by analogy. (1-2)

- Consolidated-Alphabetic: Students are more skilled at decoding and can recognize larger chunks—morphemes or syllables. (2-3+)

For years, I have been using Dr. Ehri’s research conclusions to shape my teaching, and I’ve observed that many, if not most, of my students have passed through the stages she describes.

THE FULL-ALPHABETIC PHASE

Moving to the Full-Alphabetic stage is a wonderful step, since readers don’t have to guess unfamiliar words on the basis of limited information anymore (cue reading). Now they know all or most of the letter-sound correspondences, including vowels. For this reason, Dr. Ehri calls these readers cipher readers. These youngsters’ phonemic awareness has advanced to the point where they can blend and segment sounds.

Full-Alphabetic readers can identify one sound at a time in an unknown word and blend the sounds together. This decoding can be laborious at first, so it can seem as though the children are regressing in reading. But this is a significant development because these children are fully utilizing the alphabetic nature of written language.

Children’s sight vocabularies are expanding at a great rate now, too, in a large part because of the readers’ ability to recognize the sounds of the letters within high frequency words. Even with parts of words that are nonphonetic, readers can devise tricks for remembering these anomalies. For example, to remember the spelling of friend, they could pronounce it as /fry/–/end/.

Youngsters move through this stage at different rates. Seth, described at the opening, has just moved into the Full-Alphabetic stage. He will be able to read more smoothly by the end of this phase, when decoding becomes more automatic, and he knows more words by sight. After he moves into the next phase, he will learn the -ight spelling pattern.

USE READING STAGES TO HELP READERS MAXIMIZE THEIR LEARNING

Fortunately there are three ways we can adjust our teaching to the reading phase a child is moving through:

-

-

-

- Introduce words most appropriate for that phase.

- Teach strategies for learning at that stage.

- Nudge the students toward the next phase.

-

-

HELPING FULL-ALPHABETIC READERS

1. Introduce words most appropriate for the Full-Alphabetic stage.

The most appropriate words for the Full-Alphabetic stage are phonetic, or regular, words. These are words whose letters make a predictable sound. For young children, the term phonetic also refers to the words are composed of letter-sound correspondences that the children are familiar with.

We want to expose Full-Alphabetic readers to phonetic words. If your reading instruction is tied to a curriculum, then you will obviously follow that. But if you are able to create your own words for instruction, then you will want to pin down the grapheme-phoneme (letter-sound) correspondences that your students know.

There are several steps in introducing phonetic words to your students.

-

-

-

- Assess letter knowledge

- Decide teaching order for letters

- Teach letter sounds

- Choose phonetic words for students to work with

-

-

Assess letter knowledge

Before you start presenting phonetic words for decoding, make sure that your students know the sounds of the letters in the words you create. To enter this stage, readers know many grapheme-phoneme relationships, but it’s helpful to start with a letter assessment to see which letters or correspondences you still need to teach. You can create your own assessment or use an existing one.

Decide teaching order for letters

Once you figure out which letters you need to introduce or review, teach the letters systematically. Systematic teaching means you are teaching explicitly and in an intentional order.

A mistake that some teachers make is teaching a letter a week, in alphabetical order. By the time the 26 weeks are up, the children tend to forget the first letters they learned. There are many alternatives to the letter-of-the-week approach.

- Start with initial consonants whose sounds can be easily extended (m, s, f, r, n).

- Or start with letters whose sounds are embedded at the beginning of the letter name (b, soft c, d, soft g, j, k, p, t, v, z).

- Next easiest are the consonants whose sounds can be heard at the end of the letter name (f, l, m, n, r, s).

- The most challenging letter sounds to learn are the consonant sounds whose letter names have nothing to do with the sounds (hard c, hard g, h, q, w, x). I make up silly names for some of the difficult letters (e.g., haitch, wubble you).

- Regarding vowels, I start with short vowels, because they’re the ones I teach first in my phonics lessons; but if you prefer, start with the long vowels.

Teach letter sounds

Devoting time to systematic letter work every day in PreK, kindergarten, or early 1st grade will lead to automaticity in decoding.

When I teach a letter, I present it with a key word and picture for remembering the sound (e.g., A a – apple). I have my students say, “A – a – apple – ă,” so they will associate the key word with the letter sound. This is especially wise for vowels and challenging consonant sounds.

It also helps to introduce and reinforce the letters in a multisensory way. There are many multisensory programs for introducing letters and their sounds. For example, Lively LettersTM presents the letters pictorially and teaches hand and body movements and songs for all the letters. Students can practice letter formation with magnetic letters, in sand trays, or on a Magic Slate. Read alphabet books to children, and have them read individual letter books.

It also helps to introduce and reinforce the letters in a multisensory way. There are many multisensory programs for introducing letters and their sounds. For example, Lively LettersTM presents the letters pictorially and teaches hand and body movements and songs for all the letters. Students can practice letter formation with magnetic letters, in sand trays, or on a Magic Slate. Read alphabet books to children, and have them read individual letter books.

Choose Phonetic Words for Students to Work With

Don’t wait until the children know all the letter sounds before you begin to teach phonics. You will be teaching phonetic decoding and letter knowledge concurrently. Once you determine which letter-sounds your students know, you can begin to create words with those letters. If you begin with CVC words (consonant-vowel-consonant), you will only need one vowel (usually short-a) and a few consonants to start creating words (e.g., bat, Sam). Get a double benefit by including high frequency phonetic words that the students are likely to see in their reading (e.g., Dad, am, at).

As the students learn more letter sounds, you will vary the letters in the phonetic words that you teach. It’s helpful to use a chart to keep track of the letter sounds that you have introduced.

2. Teach strategies for learning at the Full-Alphabetic stage.

Different reading researchers and educators recommend different approaches to teaching phonics.

Synthetic and Analytic Phonics

In the U.S., teachers use two main methods to teach phonetic decoding: synthetic phonics and analytic/analogic phonics.

According to Linnea Ehri, as children enter the Full-Alphabetic phase, the phonics approach they learn from most easily is synthetic phonics. Synthetic refers to the process of putting things together. In synthetic phonics, students are taught to associate each letter in a word with a sound and then blend the sounds together to decode a word.

When faced with the regular word bat, a child would say, one by one, the sounds of the letters /b/…/ă/…/t/, and then blend the sounds together to get the word bat.

With analytic phonics, however, we show children how to look at larger parts of words. They analyze the words, or take them apart. Teachers using this approach explain word families, through onsets and rimes.[i]

Children learn the -at family: bat, cat, rat, etc.

With analogic phonics, a type of analytic phonics, you show the student how to compare a new words to a words they already know. For this method to work, a child has to have some known words (sight vocabulary).

When faced with the regular words bat, a child might say, “I know the word cat is /c – at/, so this new word bat must be /b – at…bat.”

What decoding strategies should we teach to Full-Alphabetic readers?

Ehri suggests teaching synthetic phonics at the beginning of the Full-Alphabetic phase. But, toward the end of the stage, students begin to process larger chunks and can learn to use an analytic approach. Ehri also notes that children need some ability to decode letter by letter to succeed with analytic phonics.

Timothy Shanahan, who was on the Alphabetics Committee of the National Reading Panel (chaired by Linnea Ehri, by the way!), notes that, in their research review, the committee found that both synthetic and analytic phonics approaches are successful. Later, on his own, Shanahan observed that his students found it easier to begin with the synthetic approach and move later to the analytic. That echoes Ehri’s position.

My teaching has confirmed this same general tendency, so I usually start teaching with synthetic phonics. But my experience has also shown me that the best phonics approach for a student will vary, depending on the child’s strengths and weaknesses.

Not all children respond to sounding out words letter by letter. Children with sequencing problems have difficulty blending sounds in the right order. They do better using the analytic or analogic approach, with larger chunks, from the get-go. Learning word families is usually the best route for these kids.

A student with a weak sight vocabulary or poor working memory will do poorly with the analytic or analogic approach, as they have trouble comparing new words to known words, or keeping more than one word in their mind at the same time. These kids do better with synthetic phonics.

Whatever phonics approach you use, it’s important to explain to your students that not all words are phonetic. I tell my students that some words are stinkers because they don’t go by the rules.

Reading in Texts

It’s crucial to have children reading texts as we teach them decoding. Reading connected text should not wait until students know all their letter-sound correspondences. If we just teach phonetic skills, kids might conclude that the point of reading is word identification. As a result, their reading comprehension will suffer. We want children to realize that the purpose of reading is gaining meaning from the text.

Some teachers prefer using decodable texts with readers at this stage. Decodable texts are texts that consist primarily of regular words. Nonphonetic high frequency words are included, but at a minimum. In my opinion, these texts are unnatural. (The fat cat sat on the mat.) Too much time reading decodable texts may rob children from the opportunity to self-correct when their phonetic attempts do not make sense.

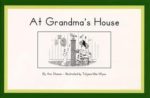

My preference is for using more natural texts that include both unfamiliar phonetic words that the children will have to decode, and enough high frequency words to make the text sound natural. Having a lot of high frequency words in a text helps build up children’s sight vocabularies, and a natural style enables readers to enjoy the story and monitor for meaning.

I wrote my Handprints books in just this way. Below is a sample of one of one of my favorite books from the series.

I do not mean to say that mine is the only correct point of view on the issue. In fact, I have used decodable text with a student who was stuck in the Partial-Alphabetic stage. He persisted at guessing words, even though he had the knowledge of letter sounds and blending ability needed to successfully decode. It was only when I had him read decodable text for a few days that he finally began sounding out the words phonetically. However, I made sure that this use of decodable text was temporary.

Decodable text can be helpful, when used temporarily, or when combined with a diet of more natural texts. The danger of students reading too much decodable text is that they will stop focusing on meaning as they read, and that they will not be adding many high frequency words to their sight vocabulary. With more natural texts, you can teach your students how to monitor for meaning, if their decoding attempts to not make sense.

No matter what kind of text you use, be sure to have the children work with phonetic decoding both both in isolation and within texts.

3. Nudge the students toward the Consolidated-Alphabetic stage.

Toward the end of the Full-Alphabetic stage, readers begin to move beyond the letter-by-letter decoding approach they have been using. Now children begin to chunk words into onsets and rimes (e.g., b-ig, rather than b-i-g) or to use analogies to read words (e.g., I know look, so this must be book). The more automatic their decoding becomes, the faster their sight vocabularies expand. The larger their sight vocabularies, the better they become at using analogies to unlock unfamiliar words. Children’s awareness of larger word parts is growing. This reading by chunks brings readers to the next stage, the Consolidated-Alphabetic stage.

To encourage students to get ready for the Consolidated-Alphabetic stage, you want to begin to introduce word parts that are larger than the single letter, with its single sound. These word parts can be onsets and rimes, morphemes, or syllables. Morphemes are the smallest meaningful parts of words (prefixes, suffixes, and roots).

You might begin to introduce word chunks such as these:

-

-

- the inflectional suffixes -s, -ing, and -ed added to known words such as look or play

- consonant digraphs th, sh, ch

- onset-rime divisions of high frequency words: -ay in day and play

- parts of early compound words: into, today, etc.

- morphemes -er, -est

-

One way students can learn about word chunks is by adding inflections to nouns and verbs. Inflections are the most common affixes, so I start with them. Inflectional endings change the tense of a verb or number of a noun. Help yourself to this chart.

Don’t forget balance!

When you teach word analysis of any kind (synthetic phonics, analytic phonics, analogic phonics, morpheme awareness, syllabication), always balance that focus with attention to reading comprehension. Learn from my mistakes! I’m a details person, so I can get hung up on teaching phonics skills and forget about the big picture, which is meaning.

The Full-Analytic stage is an exciting time to teach. We watch readers become more and more independent, and as they become more independent, their enthusiasm about reading grows. Enjoy teaching your students to decode words. Enjoy their smiles, but don’t forget balance!

Happy teaching of Full-Alphabetic readers!

References

Brown, Kathleen J. 2003. What do I say when they get stuck on a word? Aligning teachers’ prompts with students’ development. The Reading Teacher: 56(8) – 720-733.

Ehri, Linnea C. 2005. Development of sight word reading: Phases and findings. In M.J. Snowling and C. Hulme (eds.), The Science of Reading: A Handbook. UK: Blackwell Publishing, Ltd. https://doi.org/10.1002/9780470757642.ch8.

Ehri, Linnea C. 2014. Orthographic mapping in the acquisition of sight word reading, spelling memory, and vocabulary learning. Scientific Studies of Reading 18: 5-21. https://doi.org/10.1080/10888438.2013.819356.

Ehri, Linnea C. 2015. How children learn to read words. In Oxford Library of Psychology: The Oxford Handbook of Reading (Alexander Pollatsek and Rebecca Treiman, eds.), pp. 293-310. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Retrieved on 11/28/2019 from https://psycnet.apa.org/record/2015-46178-020.

Ehri, Linnea C. and Sandra McCormick. 1998. Phases of word learning: Implications for instruction with delayed and disabled readers. Reading and Writing Quarterly: Overcoming Learning Difficulties 14 (2): 135-163. https://doi.org/10.1080/1057356980140202

Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, NIH, DHHS. 2000. Report of the National Reading Panel: Teaching Children to Read: Reports of the Subgroups (00-4754). Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office.

Henry, Marcia. 2010. Unlocking Literacy: Effective Decoding & Spelling Instruction, 2nd Ed. Baltimore: Paul H. Brookes Publishing Co., Inc.

Shanahan, Timothy. 2018. Which is best? Analytic or synthetic phonics? Downloaded on 12/3/2020 from https://www.readingrockets.org/blogs/shanahan-literacy/which-best-analytic-or-synthetic-phonics

———————————————-

[i] A rime is part of one-syllable words that includes the vowel and all the letters following the vowel. The onset is the part of the word before the vowel. In bat, the rime is at, and the onset is b. Some words are just rimes (in, at).

Leave a Reply